'

After surviving seven years of war, Aya Qrai was offered a unique chance at joy: her first child, a son.

"Abdulrazaq let me live in my own world and I forgot the war — I saw the beauty of life through him," said Qrai, 19, speaking from a rebel enclave in northwestern Syria. "With all the war and all the sadness, I was full of happiness."

Abdulrazaq was born two months premature and went into intensive care at a hospital in the city of Maarat al-Numan in northwestern Syria. He died 16 days later, after airstrikes badly damaged the facility in Idlib Province on Sunday and forced the evacuation of at least 10 newborns.

Abdulrazaq died from lack of oxygen before he reached another hospital, according to his family.

Video shot on Sunday in the aftermath of an attack that rebels and observers say was carried out by a Russian warplane shows newborns being rushed from the damaged building.

Tearful and exhausted, Aya Qrai says she wants to die.

“We Syrians are not allowed to smile and to live a normal life,” she said, sitting close to her husband, Hamoud. “When I decided to live and to challenge the war [by having a baby], the airstrike took my baby away from me.”

A hospital in nearby Kafr Nabl was also bombed Sunday, forcing the evacuation of patients.

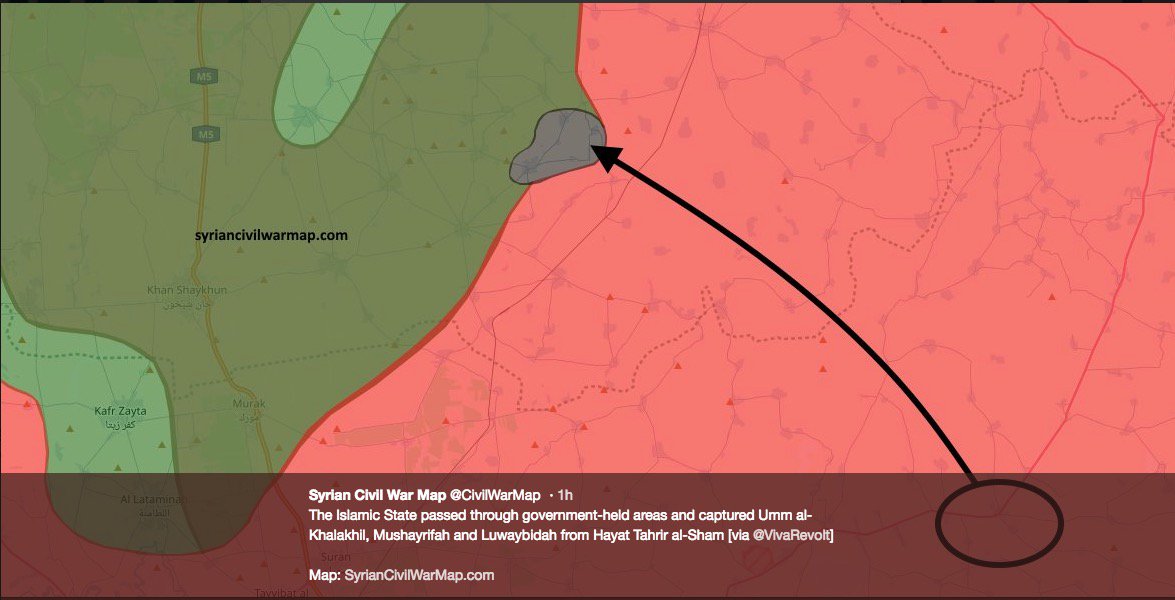

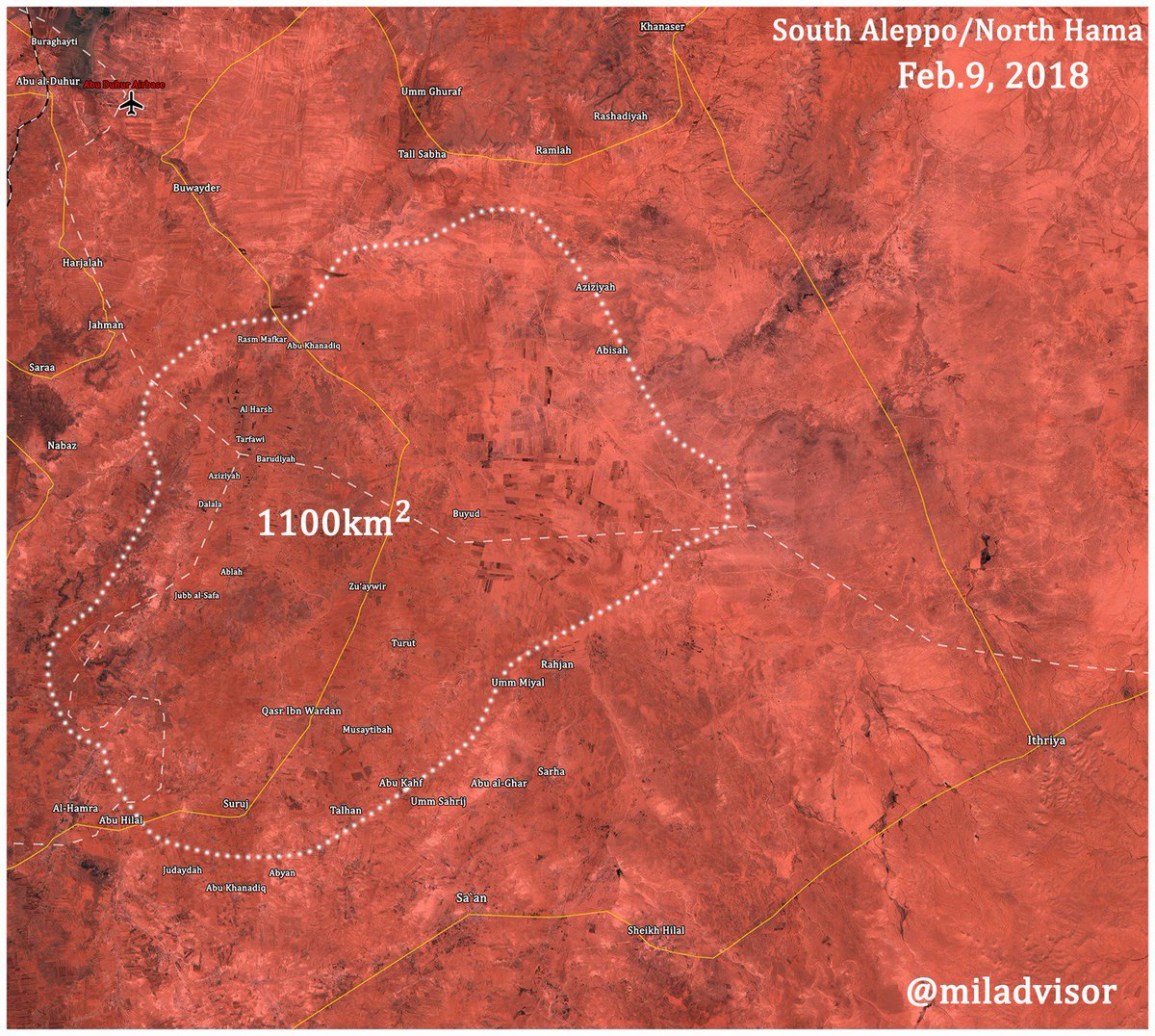

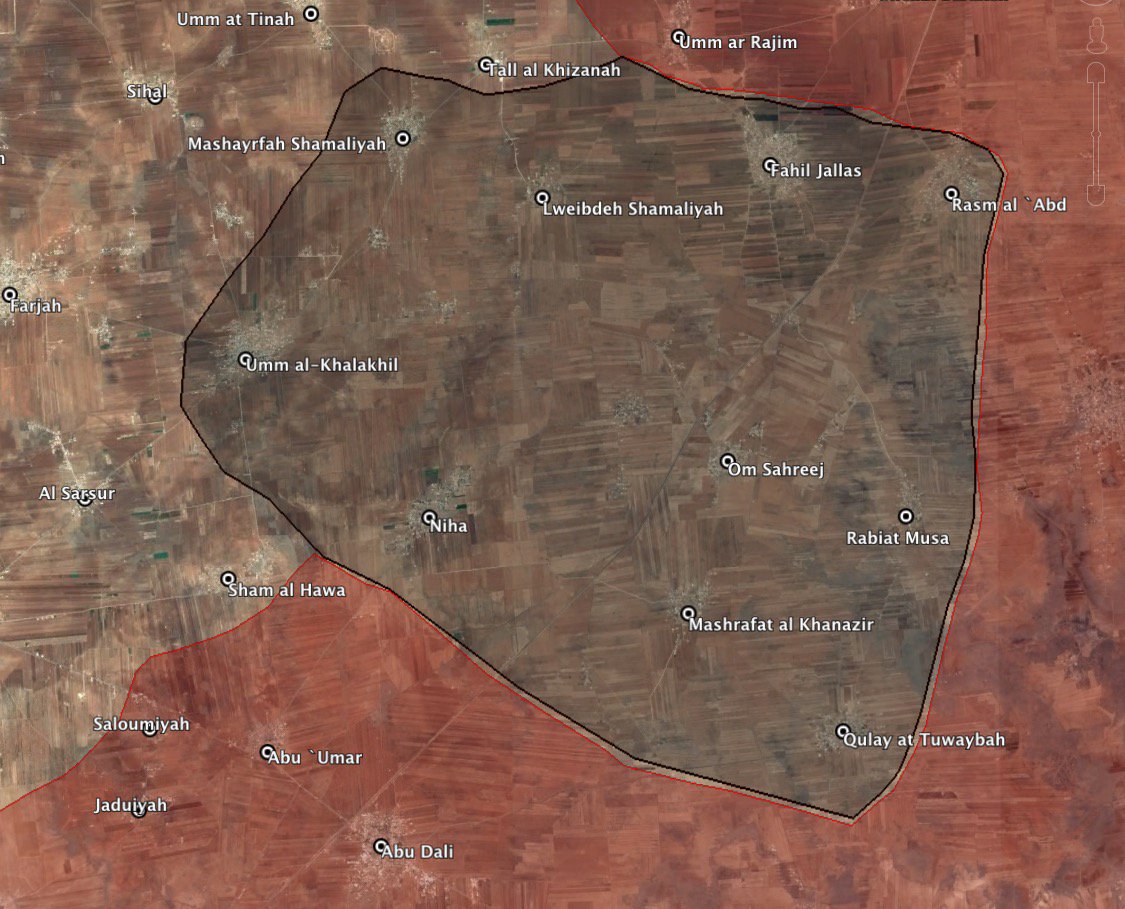

The shelling of the hospitals and other areas where civilians are trapped comes amid intensifying attacks on rebel-held areas near the city of Aleppo and the capital, Damascus.

The Qrai family’s grief is just one piece in a mosaic of tragedy created by Syria’s civil war, which started as pro-democracy street protests against the rule of President Bashar al-Assad in 2011. The conflict quickly spiraled into a full-fledged conflict that has killed hundreds of thousands of people and forced millions from their homes.

The Qrais are among some two million people now living in Idlib — where fighting is forcing civilians to move constantly to escape fighting, according to the United Nations. Two pro-government villages in Idlib were also being besieged by rebels, the U.N. announced on Tuesday.

When asked if the couple had a message for the world, Hamoud Qrai angrily interjects: “Sir, how many messages do we have to send? How many appeals do we still have to make to stop the killing? We are being killed by a dictator who wants to rule us by force.”

“Who on earth would target a hospital?” he said.

This week, the U.N. called for an immediate humanitarian cease-fire in Syria of at least a month after heavy airstrikes claimed scores of lives.

Aid workers, meanwhile, warn that rebel areas are not receiving desperately needed deliveries.

"For the last two months we have not had a single convoy,” said Panos Moumtzis, assistant U.N. secretary general and regional humanitarian coordinator for the Syria crisis. “This is really outrageous." '